Indian Background Index

World Rejection,

World Affirmation,

and Goal Displacement:

Some aspects of change

in three New Religious Movements of Hindu origin.

Björkqvist, K (1990):

World-rejection, world-affirmation, and goal displacement: some aspects of change in three new religions movements of Hindu origin.

In N. Holm (ed.), Encounter with India: studies in neohinduism (pp. 79-99) - Turku, Finland. Åbo Akademi University Press.

Books and articles about new religious movements (NRMs) often present the latter as if no changes whatsoever occurred within the movements with respect to their relations to surrounding society (e.g., Haack, 1979; Mangalwadi, 1977; Needleman, 1978). Nothing is further from the truth. In fact, several (if not all) of the NRMs are subject to rapid change, and any study which fails to recognize this state of affairs is inadequate. Furthermore, the changes NRMs undergo should be of particular interest to sociologists, since they facilitate an understanding of the role of these movements in today's pluralistic, post-industrial society.The present paper will attempt to examine change in three religious or quasi-religious movements of Hindu origin: Transcendental Meditation (TM), the International Society of Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), and the Divine Light Mission (DLM). Although other important aspects of change (such as organizational ones) should be recognized, only two will be considered here:

1) change in the degree of deliberate divergence from the norms of the mainstream society, i.e. - in the terminology of Wallis (1984) - world-rejection, and

2) change of goals.In the present paper, Wallis's (1984) conceptual framework will be analysed in some detail . Goal displacement, a concept utilized by Gross and Etzioni (1985, pp. 9-27) for describing change within non-religious organizations, economical as well as political, will also be introduced and adopted in this particular context.

Wallis's model: critique and modification

When a NRM emerges, it relates to the surrounding society in one way or another. It may criticize or reject it, partly or wholly. It may also accept and strengthen attitudes and behavioral patterns prominent within the surrounding society. Every movement may, at least theoretically, be estimated on a scale measuring its degree of world-rejection/world-affirmation.

Wallis (1984) describes three types of religious movements: world-rejecting, world-accommodating, and world-affirming ones. A world-rejecting movement views the prevailing social order as having departed from God's prescriptions and the divine plan. The world, according to this kind of movement, is evil, or at least materialistic. It condemns modern urban society and its values, particularly that of individual success. Rather than pursuing a life of self-interest, a world-rejecting movement typically requires a life dedicated to "egolessness", which may take the form of service to the movement or the guru, denying the individual's own interests or needs. World-rejecting movements quite often tend to be millenarian, expecting the movement to sweep the world, and, when everyone has become a member, or at least, when members are a majority of the world's population, then a new world-order will begin (Wallis, 1984, pp. 10-20).

The world-accommodating movement (ibid., pp. 35-39) draws a clear distinction between the spiritual and the worldly spheres. Although it may strive to reinvigorate the individual for life in mainstream society, it has few or no implications for how that life should be lived. It thus accommodates to the world, but it does not reject or affirm it.

The world-affirming movement (ibid., pp. 20-35) may actually lack most of the features traditionally associated with religious movements. It may have no ritual, no official ideology, perhaps no collective meetings whatsoever. It does not view the world contemptuously; on the contrary, it may see it as possessing highly desirable goals. It simply claims that it has the means to enable people to unlock their hidden potential, whether spiritual or mental, without the need to withdraw from or reject the world.

As examples of world-affirming movements, Wallis mentions est and TM, while ISKCON, the Unification Church and Children of God are given as examples of world-rejecting movements. Wallis obviously finds it hard to find good examples of world-accommodating movements among the NMRs. The only one he discusses at length is the neopentecostal movement, which is of Christian origin. The only non-Christian, new movement he accepts as an example is Pak Subud, which he only mentions in one sentence without further comment.

Although Wallis points out important distinctions between movements, there are certain problems with his model. The first and most serious objection on the part of the present author is that he does not clarify well enough the "spatial" relationship between the three types of religious movements. He presents them in the form of a triangular diagram, giving the impression that their relationship to each other is multidimensional. He places certain movements (Jesus People, Meher Baba, and DLM) in the middle, suggesting that they are in some way equally close to all three types (ibid., p. 6, fig. 1). For this to be possible, the model must be multidimensional, since equidistance to three extremes requires at least two-dimensionality.

On the other hand, he suggests that the three types form a one-dimensional continuum, with world-rejecting movements at one extreme, world-accommodating movements in the middle, and world-affirming movements at the other extreme (ibid., figs. 3 and 4 at pp. 80 and 83, see also p. 20). It is impossible to have it both ways.

The problem seems to be partly that Wallis has been influenced by Yinger's (1970) typology of sects (acceptance, aggressive, and avoidance sects; see ibid., fig. 2 at p. 7, with Yinger's typology presented in triangular format). Wallis, in fact, mentions explicitly that there are similarities between his model and that of Yinger (ibid., pp. 9-10). Wallis would perhaps have been better off with a one-dimensional model, since this is the way in which he in fact generally treats his concepts.

Another complication is the concept of world-accommodation. Although it is theoretically clear what the concept stands for, it is by no means obvious what it implies in practise. Firstly, Wallis himself, as previously pointed out, has difficulties in finding good examples of world-accommodating movements. Secondly, if the latter are located in the middle between the two extremes of world-rejection and world-affirmation, an impression Wallis sometimes seems to give (ibid., pp. 80-83), then the term is unambiguous, but at the same time it becomes more or less unnecessary as a concept. Wallis himself seems to oscillate between the options of a one-dimensional and a multidimensional model. I may not do him full justice by this criticism, but this is undoubtedly the impression obtained by the reader of his otherwise excellent work.

Wallis's description of world-affirming movements also poses some questions. He describes them as typically lacking the features traditionally associated with religion, such as a church, ritual, and collective worship (ibid., 20-35). In fact, there is no logical impediment to being a church organization and being a world-affirming movement. The most world-affirming religious movement we know of in today's Western societies - the Christian churches and their denominations - are very church-like indeed. The examples Wallis gives of world-affirming movements (est and TM) may have led him astray. What Wallis describes are in fact the characteristics of what Stark & Bainbridge (1978) have called client cults. But it is by no means necessary for a world-affirming movement to be a client cult - the most typical ones are, as previously mentioned, actually the established churches and denominations.

Wallis may, however, be right in claiming that most of the new world-affirming religious movements have the typical features of client cults. If this is so, it is interesting in itself. It may have something to do with the particular role of religion in the pluralistic type of society we have today. This question will be reconsidered in the final paragraphs of this article.

Despite these critical comments, the present author still considers Wallis's analysis extremely important and perhaps the most valuable contribution to date towards the understanding of change in NRMs. In the following, his concepts of world-rejection and world-affirmation will be adopted, with modifications, for the analysis of change within TM, DLM, and ISKCON. The concept of world-accommodation will be dropped, and world-rejection and world-affirmation will be treated as two extremes in a one-dimensional, bipolar model.

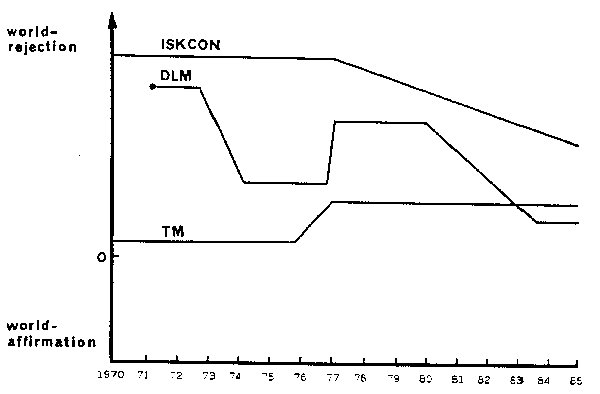

Fig. 1. Fluctuations through time (1970-85) on the dimension world-rejection/world-affirmation for TM, DLM, and ISKCON.

Fig. 1. presents fluctuations through time on the dimension world-rejection/ world-affirmation for TM, DLM, and ISKCON. A word of caution is required: these curves are naturally only very crude estimations of major trends. The dimension may be impossible to measure with exact quantitative methods. ISKCON and DLM have so far been fairly hostile towards objective scientific study conducted by outsiders, which makes the distribution of questionnaires difficult. These estimations are based on participant observation during meetings of these movements, interviews with key informants, and a thorough study of the literature. Nevertheless, the interpretation may always of course be subjected to debate.

Deviant norms of behavior, from the point of view of mainstream society, are used as the indication of high world-rejection. The behavior may consist of deviant dress or hairstyle, a special language or jargon incomprehensible to outsiders, unusual ways of living, such as in ashrams or collectives, non-traditional diets (e.g., vegetarian or Indian food), and goals in life different from the usual career orientated goals cherished within mainstream society.

Change within ISKCON

From this point of view, it may be concluded that ISKCON has been very world-rejecting indeed throughout most of the 70's, having deviant norms on all the variables mentioned above. After the death of Srila Prabhupada, the guru of ISKCON, in 1977, however, things have greatly changed. Prabhupada had not given clear directions about authority within the movement after his own death. He had vaguely mentioned that devotees might turn to his "godbrother" (=brother disciple of his own guru) Sridar Maharaja in India for spiritual direction. Some did that, but these were a minority. Prabhupada had also, some years before his death, established a Governing Body Commission (GBC), consisting of 11 "gurus", all Westerners, who each govern their own zone of the world. The movement is threatened by a certain degree of fragmentation, since the 11 gurus may have slightly different interpretations of ideology and norms (Sjöblom, in the present volume). Overall, there has been a slight turn towards less world-rejection, although for a large number of devotees, even this has not bean enough. Obviously tired of alienation from society-at-large, they want an even greater degree of world-affirmation, and they do not conform to the direction of the gurus. Many have moved out from the temples and collectives. They dress conventionally, although they are still vegetarians, chant the Hare Krishna mantra, and consider themselves devotees.

Change within DLM

DLM has shown much greater changes, and even oscillations, on the dimension of world-rejection/world-affirmation. Although never quite as world-rejecting as ISKCON (it never for instance adopted Hindu clothing or shaved heads), it started off in the West in 1971 as a clearly millenarian movement. The leader, Guru Maharaj Ji, claimed that he was going to establish peace in the world during his lifetime. There were many Hindu traditions, such as arti and darshan, within the movement, and most followers were vegetarians. Some, but not all of the followers, who called themselves premies ("lovers"), lived collectively in ashrams. Meetings, satsangs, were held every evening.

In 1974, Maharaj Ji got married to a Westerner. The marriage was not approved of by his mother and two of his elder brothers, nor by many of his Indian devotees. There was a split within the movement, with all the Western disciples accepting Maharaj Ji's authority, while only some of the Indian devotees did so. It is obvious that it was also partly a question of policy: Maharaj Ji wanted to "Westernize" the movement. He disposed of many Hindu traditions, put less emphasis on ashrams, organized the movement in a Western fashion with a large headquarters, and made serious attempts to become more accepted by mainstream society. There was a strong change towards greater world-affirmation, but some of these changes were not really successful. His attempts to normalize relations to society-at-large were not noticed by the press, which continued to write negatively about the movement. Since then, Maharaj Ji has avoided publicity.

In 1976, Maharaj Ji declared that he felt that the organization had come between his devotees and himself, and he disposed of the headquarters altogether. During the latter half of the 70's, the movement clearly returned towards greater world-rejection, although perhaps not reaching the same level as in 1971-73. The millenarian ideology had lost its credibility owing to a slowdown in the expansion rate, and the millenarian jargon gradually disappeared completely. Emphasis was placed on devotion to the guru, ashram life was again encouraged, and satsang meetings were arranged every evening.

In 1980, Maharaj Ji took a new initiative: he declared that he wanted to get rid of all the "religious" aspects of the movement, in fact, he wanted no movement whatsoever. All ashrams were abolished, and people who had been living in them in some cases for 10 years or more suddenly found themselves back to normal life. He abolished all satsang meetings. Divine Light Mission as an organization was also abolished. Most followers stopped being vegetarians, although to a greater extent they continued the practice of meditation. There are still meditation teachers who initiate people into the meditation techniques known as "Knowledge", and new followers are still gained. Since there are no meetings, no ashrams, and in most towns - even no centres, the nature of the movement has drastically changed. Maharaj Ji does not call himself a guru anymore, and he points out that he is not perfect, but human.

The changes during the 80's were gradual and not so swift as during the period 1974-76. The followers were also slow to adapt to the changes requested. Although Maharaj Ji still has a following of about the same size as before, DLM has moved very close towards the middle point between world-rejection and world-affirmation.

Change within TM

As Woodrum (1977) has pointed out, TM has gone through several distinct phases. Two of these (a "mystical" phase in the early 60's, and a "cosmic consciousness" phase in the late 60's) will be disregarded here, in order to limit consideration to developments since 1970. It is evident, however, that TM would have identified itself with a higher level of world-rejection during the 60's than during the early 70's.

In the early 70's, TM came very close to the middle point between world-rejection and world-affirmation. It claimed not to be a religion, but a scientific technique which brought, when practiced, a greater capacity for relaxation and stress reduction, and claimed to improve the creative intelligence of practitioners. It focused its marketing strategy on proving this by scientific studies (e.g., Wallace, 1970) of the beneficial consequences of meditation.

Outwardly, there was nothing to distinguish a TM practitioner from other people: no special dress, or unusual hairstyle; vegetarianism was not prescribed, and hardly practiced, except by a minority. A certain "jargon" was, however, prevalent within the movement.

From 1976 onwards, the movement was radicalized. It introduced its "World Government", clearly indicating its intention of reforming the world, although by peaceful means. It started its well-known siddhi programme, teaching people how to levitate and acquire other supernatural powers. The reason for this change will be discussed later on in this paper.

The source of change: The leader or the followers?

When change in the degree of world-rejection occurs within a religious movement, it may be due to either of the following two sources:

1) a change in attitude in the leadership,

2) a change in attitude among the followers.Regarding DLM, it seems that the relatively large oscillations in that particular case are mainly due to direction from above, i.e., change within the leadership. Obviously, the movement towards greater world-affirmation during 1974-6 was a conscious policy in order to attract other people besides drop-outs from the Establishment. The greatest spokesman for this policy, however, was Maharaj Ji's right hand at the time, Bob Mishler. In 1976, he was sacked, and Maharaj Ji took total control of all organizational aspects. The turn towards world-affirmation during the 80's was, on the other hand, instigated by Maharaj Ji himself. It was also, however, a response to real needs felt by the lay (non-ashramite) followers, who were becoming increasingly middle-aged, with families and responsible jobs. Ashram inhabitants, on the other hand, were slow to respond to the suggestion to abandon the ashrams and satsang meetings. The cause for the latter transformation may thus be described as a mixture of change within the leader and among the followers.

Regarding ISKCON, the sources of change seem to have been predominantly within the followers: When Srila Prabhupada was still alive, he was driving a strict, orthodox hinduistic line, leaving little room for ambiguity. The Western lifestyle was considered decadent, and the main reason for man's unhappiness. However, after his death, the pressure from mainstream society seems to have forced his followers towards greater world-affirmation, especially in the absence of strong, directive leadership.

In the case of TM, changes of direction seem to have been mainly outlined by the leadership. The reason for this may be sought in the fact that TM primarily is a client cult (Stark & Bainbridge, 1978), and the consequences of this fact will be discussed in more detail in the section on goal displacement.

Regression towards the mean of social norms

An examination of the historical development of religious movements suggests that the most common direction of change in the long run (excluding short term oscillations) is towards greater acceptance and affirmation of the world. This phenomenon is well known within sociology, ever since Niebuhr (1929), and it has often been alluded to as the process of denominalization, in some cases as institutionalization. Talking of non-Christian religious movements, however, the term denominalization does not sound applicable. Institutionalization, on the other hand, refers to organizational features of the movement, but not to normative ones. The question of affirmation or rejection of the world is normative to its nature. If one wishes to stress the fact that the change concerns norms, one could perhaps use the tern, renormalization. This, however, implies that a person has at one point been accepting certain norms, then rejected them, but later started to accept them again. It is not necessarily true that sectarians have initially accepted the norms of mainstream society although this is perhaps most usually the case - they may in fact have rejected them all from the beginning.

A comparison can be made with the psychological concept of regression towards the mean, describing the statistical fact that children to parents who are extremely high or low on any normally distributed property, such as height or intelligence, tend to be less extreme than their parents (Krech et al., 1982, p. 754). A parallel may be drawn to the development of religious movements, such as sects. First generation sectarians usually hold strong convictions: they have joined the sect by their own free will, while second generation sectarians are born into the movement, and are likely to move in the direction of the mean of the norms of mainstream society (Yinger, 1970, p 266 ff.).

In fact, a change towards the mean of social norms may occur already within the first generation sectarians, as they become older and reach middle age, especially if they joined the sect as relatively young. If the sect cannot offer job opportunities to its members, the latter will have to spend considerable time together with nonmembers in the context of their work, and friction between contradictory norms will occur. Besides this, the plausibility structure supporting the sect's ideology may be damaged due to, e.g., prophesies or other claims which were not fulfilled, and all of this is likely to decrease fervor. It is thus a reasonable prediction that ten year old members of almost any religious movement (not living in isolation from the rest of the society) tend to be less devoted to its cause than new members.

It is important to emphasize that a regression towards the mean of social norms is by no means a necessity in all cases. If a religious movement succeeds in isolating its members from society-at-large, for instance by establishing alternative societies, a high degree of world-rejection may be maintained for long periods of time. For the Amish people, as well as for the Laestadian Christians in Northern Finland, it has been possible to retain a high degree of deviant social norms for generations.

The friction between the movement's social norms and those of mainstream society may also lead to splitting or fragmentation within the movement. One part of the membership may want to become world-affirming, while others wish to preserve a high degree of world-rejection. Such a case can be observed within the latest developments in ISKCON, after the death of Srila Prabhupada.

Goal displacement

A concept which may help in shedding additional light on change within NRMs is that of goal displacement. It was coined by Gross & Etzioni (1985, pp. 9-27) when they wanted to describe a particular type of change in non-religious organizations, economical as well as political. The phenomenon of goal displacement was described much earlier by Mischels (1911) in analyses of change within German trade unions, although he did not use this particular concept.

Goal displacement becomes opportune when a movement becomes dissatisfied with its established goal, although the movement does not want to dissolve itself, since it has already gained momentum as a functioning entity. It is, if nothing else, in the interest of its leadership that it continues to exist.

The reasons why the movement's goal needs to be changed may vary - the most obvious being that the goal does not seem to be realistic, or that it does not feel attractive any longer. As an example, we may choose the development of the social democratic parties in Europe during this century. To begin with, their goal was the socialization of all private companies and the abolishment of capitalism, not through revolution, as the communists suggested, but by democratic means. Today, the idea of having only state owned companies in a nation does not seem very attractive. Social democratic parties in Europe have over the years silently abolished the idea of socializing all private companies, although the principle may still be written in their official party programmes. Now, they try instead to improve the conditions of poor people by other means, such as progressive taxation, extensive social security and educational programmes. One goal has been displaced by another.

Goal displacement becomes particularly necessary when the survival of the organization becomes more important than the original goal it was established to obtain. A restaurant may start with the intention of offering only vegetarian food. After a few years, however, it may turn out that this policy does not pay. The owners may be economically involved with debts and interest to pay, and there may also be emotional involvement. The original goal may seem less important than the survival of the restaurant. They may, accordingly, decide to start offering other kinds of food besides vegetarian, in order for the restaurant to survive.

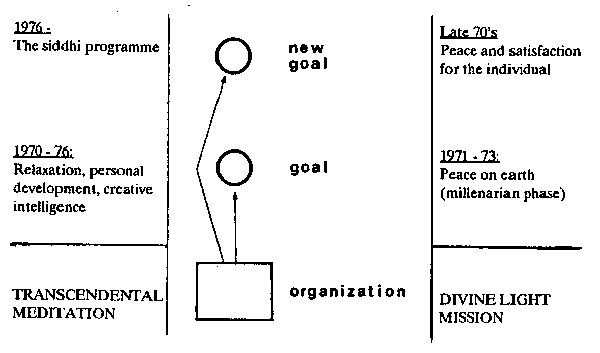

When the NRMs are examined, processes of goal displacement may easily be discovered (cf. fig. 2). DLM, for instance, during its early years in the West, had clearly millenarian features, proclaiming that Guru Maharaj Ji was the savior who would establish peace in this world during his lifetime. After the unsuccessful programme in the Houston Astrodome in 1973, and the crises within the movement after Maharaj Ji's marriage in 1974, the millenarian aspects were diminished, and they disappeared completely in the late 70's. The focus turned towards the establishment of individual rather than world peace (Björkqvist 1982).

Goal displacement is even more obvious within TM. In the late 60's, TM recruited from the youth counter culture, the drop outs. Large numbers of these people were following the example of the Beatles, who had become practitioners of TM, and Hindu philosophy and meditation came into vogue. The goal towards which the TM movement claimed to strive, or the product it offered to provide, was "cosmic consciousness", a famous concept in the late 60's. Cosmic consciousness was something the youth counter culture had been trying to obtain by the help of mind expanding drugs such as LSD. Meditation was regarded as another, safer and more natural, way of getting "high".

Fig. 2. Examples of goal displacement during the period 1970-85 within two new religious movements of Hindu origin: TM and DLM.

After the well-known dissertation of Wallace (1970), which suggested that meditation may indeed have beneficial physiological effects, the TM movement changed its jargon. In the hope of recruiting a larger following from other strata of society, i.e. from people with faith in science, it started to encourage scientific research on TM. It presented as its goal the offering of products such as relaxation, reduction of stress, and creative intelligence (Woodrum, 1977). Whether this was a case of actual, or only quasi, goal displacement is open to debate. There is good reason to believe that an inner core of the movement actually had more spiritual goals all the time (e.g., WaIlis, 1984, p. 94).

In the mid-70's, TM made another turn, this time towards greater world-rejection. It established a "World Government" of its own, with ten ministeries. It began its famous siddhi programme, claiming that it would teach people to levitate and to acquire other supernatural powers. This was another case of goal displacement.

The case of TM's twist towards greater world-rejection requires further explanation, since it runs counter to the usual developmental trend of religious movements, i.e. that of conventionalisation and reformalisation. If we examine it in terms of product selling and marketing, it makes sense, however. In the late 60's, TM tried to reach (sell its products to) the youth counter culture. A certain kind of rhetoric was used. In the early 70's, while most other NRMs of Hindu origin still recruited from that particular stratum of society, TM tried to reach customers from the Establishment, such as doctors, lawyers, and scientists.

What is significant when change within TM is compared with change within DLM and ISKCON is that TM has always changed in search of customers, while the other two have changed basically because their followers and/or leadership have changed their lifestyle or attitudes. This is extremely interesting, but also intriguing. Why is it so? The explanation offered here as the most probable one is that TM has always been a client cult, according to Stark's & Bainbridge's (1978) classification, with loose membership. It is actually wrong to talk about membership at all, except for an inner core of devoted followers (meditation teachers) of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. TM has only clients, i.e. people who buy the product, learn to meditate, or buy the siddhi programme, and then go on with their own life. In order to flourish, TM always has had to look for new customers, whereas DLM and ISKCON - at least during the 70's - had distinct members or disciples, who devoted themselves to the movement. They were cult movements, according to the classification system of Stark & Bainbridge (1978).

Change in TM and the Stark & Bainbridge theory of religion

Bainbridge & Jackson (1981) have analysed the radicalization of TM in the late 70's`in accordance with the Stark & Bainbridge (1978) theory of religion. This theory suggest that when an organization promises natural rewards, but fails to provide them, it promises supernatural compensation instead. This seems to fit, at least superficially, the data for TM, but it does not necessarily fit with all the facts. Did TM really fail? It promised relaxation, better life satisfaction, etc. There is a large amount of research showing that TM in fact managed reasonably well in improving the life quality of those people who took up meditation seriously (see Orme-Johnson, 1977, for a collection of scientific papers on the effects of TM. There has been criticism of this kind of studies, such as that of Staal, 1975, pp. 106 113, but the positive effects of meditation can hardly be altogether denied).

The problem in the case of TM is that once the product is sold, the customer does not come again. He already has it. However, he may come again to bay a new product from the firm, such as the siddhi programme. He returns, not because TM is a failure, but because he has at least some trust in the movement and likes the meditation technique. Simultaneously, while old customers were attracted by a new product, TM also appealed to new potential customers with an interest in supernatural matters.

Stark (1981) has analysed Synanon's transformation from an encounter group with the goal of rehabilitating drug addicts into a religious movement in its own right, in the same way as Bainbridge & Jackson (1981) analysed TM's radicalization in the late 70's. The explanation is epistemologically very problematic. Again, it may seem superficially to fit the facts (Wallis, 1986, p. 96, claims that it does not); but even if it did, it still does not support the general model of the Stark-Bainbridge theory of religion, or its applicability in this particular case. There must be literally hundreds of rehabilitation centres for drug abusers, utilizing encounter group techniques, spread al! over the world. Some of them have probably been failures, and others perhaps successful. If the explanation Stark suggests is correct, why have all the failures not become religious movements? Proving one case does not prove very much.

This does not imply that the basic principles of the Stark-Bainbridge theory of religion are necessarily wrong: The present author agrees with the idea that human beings are reward seekers by nature, and when the natural rewards necessary for a harmonious life become impossible to obtain, man looks for supernatural compensations. It does not follow from this however that the failure of non-religious organizations automatically turns them into religious movements. A turn towards religiosity is only one possible outcome of many, and it is naturally of great interest to investigate why some organizations choose this solution, while others do not. Other factors besides failure must certainly be found. One such factor is perhaps the personality of the leader: one leader may be supernaturally inclined, while others are not; additional factors may be context bound, varying greatly from one situation to another.

Final remarks

Is it possible to predict anything about the future direction of TM, DLM, and ISKCON?

It has been stated above that the most likely direction of change is that towards greater world-affirmation. If a movement wishes to maintain a high degree of world-rejection, it must then also adopt an isolationist policy, i.e., it must create alternative sub-societies, collectives or the like, and preferably create work opportunities for its members so that they will not have to experience the friction of diverging norms in daily contact with nonmembers. None of the three movements in question seems, at the moment of writing (1988), to be pursuing this kind of policy.

ISKCON is at a critical stage. It is possible that one branch, or some of its subgroups, will attempt to maintain a relatively high degree of world-rejection, while the major part of the membership is moving rapidly towards renormalization. ISKCON is not getting very many new followers at the moment. Originally, in the late 60's and the early 70's, it recruited from the youth counter culture, which consisted of people who did not very much mind, or were perhaps even attracted by, its high degree of world-rejection. Today, there is no longer any counter culture to recruit from, and the yuppies of the 80's are not very likely to shave their heads and go chanting in the streets. If ISKCON chooses a lower profile, closer to the middle point on the dimension of world-rejection/wold-affirmation, it may be able to recruit a new following.

ISKCON's problem is also very much an organizational one, because of the death of Srila Prabhupada. It is now governed by the GBC (see above), consisting of 11 "gurus" with additional members. If it manages to solve its authority problem, and focus future policy on respectability and world-affirmation, without losing its exclusivity, it may have a chance to survive and become what Yinger (1970, pp. 266-273) has called an established sect.

DLM (which is not called DLM anymore, although the name is retained here for the sake of comprehensibility) has changed enormously during the 80's from what it was during the late 70's. It has still retained many of its old hard core members, but these now tend to live a "normal" life. Since there are no meetings, or special communal activities, old members do not meet very much. New people are still being initiated into the meditation techniques - according to what by the present author considers a reliable source of information, 7,000 in the West and 14,000 in India (within the fraction loyal to Maharaj Ji) were initiated during 1986. This sounds large, but since there is no formal organization, it is impossible to estimate how many of these actually practise meditation regularly. DLM has, as a matter of fact, almost changed into what Bainbridge & Stark (1978) calls a client cult, with clients or customers rather than followers. The new people it attracts are predominantly middle-aged, and not young, as was the case in the 70's.

Whether this trend will continue is impossible to say, although it seems likely at the moment. DLM has nevertheless been characterized by swift oscillations before, and matters depend very much on the personal development of the leader, Maharaj Ji. He is a charismatic person, and very much in charge. The present trend may be regarded as a "sound" development in comparison with earlier phases of the movement. It is likely to attract some new followers, since it gives the individual a great degree of freedom to live his or her own life. Today's follower or client is not, however, likely to be strongly involved or dedicated as was the case previously in the movement.

TM is, as mentioned, in a phase of higher world-rejection than in the early 70's. The present author has doubts about whether the siddhi programme will be successfull, since customers will in the long run become dissatisfied if they do not learn how to levitate as was promised. TM has previously been characterized by frequent cases of goal displacement. Such changes may also occur in the future. TM has proved to be a flexible, well organized movement. It has a functioning economy, has established universities of its own, and is rather dependent more on the technique than on the guru. It therefore has a better chance of avoiding crises, such as the death of the guru, than ISKCON and perhaps also DLM. The latter is still, regardless of its present high world-affirmation, very dependent on its leader.

An interesting fact is that two of these three movements (TM and DLM) are at the moment primarily client cults. This may be the reflection of a major trend within NRMs today, which also seems understandable from the sociological point of view. In the large cities of Europe and USA, I have noticed that sect-like NRMs, so frequent during the 70's, seem to be diminishing. They also recruited followers from the counter culture, which was in itself world-rejecting.

Today, the counter culture has largely disappeared, and a "yuppie" lifestyle is now prevalent among young people. At the same time, there is an upsurge of alternative therapies, self-development techniques etc., which one may learn without dedicating one's whole life to a guru. Client cults definitely seem to be more vogue than sects at the moment. Ideologically, it is the "cult of man" (Westley, 1978) rather than the cult of God which has wind in the sails.

It has often been claimed that in the pluralistic, post-industrial society of today, religion has been increasingly "privatised", i.e. moved from the public into the private sphere (Björkqvist, Holm & Bergbom, in the present volume). People have the possibility of choosing their religion in the same way as they choose what clothes to wear or what restaurant to go to. In present day society, religion is not only becoming a private matter, but as a consequence of this, it has also to large extent become a product, which can be bought and sold. In this kind of society, the client cult type of movement fits in very well, as long as it has something to offer. In this context too, competition may wipe the board of unsuccessful enterprises. If movements manage to find their own ecological niche, i.e. find something to offer to at least a subgroup of society, they may survive.

References

Bainbridge, William S. & Daniel H. Jackson

1981 The rise and decline of Transcendental Meditation. In Bryan R. Wilson (ed.), The social impact of new religious movements. New York: Rose of Sharon Press, pp. 135-58.

Björkqvist, Kaj

1981 Divine Light Mission. In N. G. Holm, Kirsti Suolinna and Tore Ahlbäck (ed.), Aktuella religiösa rörelser i Finland. Åbo: Åbo Academy Press. pp. 245-263.

Björkqvist, Kaj, Nils G. Holm & Barbara Bergbom (in the present vol.) 1990 The relationship between the acceptance of Hindu thought and personality variables: A cross-cultural study.

Gross, Edward & Amitai Etzioni 1985 Organizations in Society. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. Prentice-Hall.

Haack, Friedrich-Wilhelm

1979 Jugendreligionen. Munich: Claudius & Pfeiffer.

Krech, David, Richard S. Crutchfield, Norman Livson, William A. Wilson jr & Allen Parducci

1982 Elements of psychology. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. (4th ed.)

Mangalwadi, Vishal

1977 The world of the gurus. New Delhi: Vikas.

Mischels, Robert

1962 (1st ed. 1911) Political parties. New York: Free Press.

Needleman, Jacob & G. Baker (eds.)

1978 Understanding the new religions. New York

Niebuhr, H. Richard

1929 The social sources of denominationalism. New York: Meridian.

Orme-Johnson, David W. (ed.)

1977 Scientific research on the Transcendental Meditation program: Collected papers. Weggis: Maharishi European Research.

Sjöblom, Ronny (in the present volume)

1990 When the master dies: conflict and development within the Swedish ISKCON.

Staal, Frits

1975 Exploring mysticism. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Stark, Rodney

1981 Must all religions be supernatural? In Bryan R. Wilson (ed.), The social impact of new religious movements. New York: Rose of Sharon Press, pp. 159-177.

Stark, Rodney & William S. Bainbridge

1978 The future of religion. Secularization, revival, and cult formation. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press.

Wallace, Robert K.

1970 The physiological effects of Transcendental Meditation. Diss., UCLA. Also published by MIUPRESS.

Wallis, Roy

1984 The elementary forms of the new religious life. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

WestIey, Frances

1978 "The cult of man": Durkheim's predictions and new religious movements. Sociological Analysis, 39, 2: 135-45.

Woodrum, Eric

1977 The development of the Transcendental Meclitation movement. The Zetetic, 1, 2: 38-48.

Yinger, J. Milton

1970 The scientific study of religion. London: Macmillan.

Please don't hesitate to send feedback and suggestions to jmkahn@club-internet.fr