|

|

|

Religious

Ecstasy |

|

|

|

RELIGIOUS ECSTASY Based

on Papers read at the Symposium on Religions Ecstasy held

at Distributed

by |

|

In everyday language, the word "ecstasy" denotes an intense, euphoric experience. For obvious reasons, it is rarely used in a scientific context; it is a concept that is extremely hard to define. Ecstasy-seeking religious movements have always existed, and they seem today to be as numerous as ever. There is perhaps no reason yet to abandon the concept entirely. I will not attempt to define the term ecstasy here, but I will say that I consider ecstasy, mysticism and trance to be partly overlapping concepts. In mystical experience, there is always an element of ecstasy, although the presence of this element is not, in itself, enough to justify calling an experience mystical. In trance, there is often, but not necessarily, an element of ecstasy. In the literature, trance has nonetheless often been used almost synonymously with ecstasy. Furthermore, an experience can be ecstatic without being either mystical or trance-like. An experience can also be ecstatic without having any religious connotation whatsoever. Since the borderline is so hard to draw, I will in this discourse consider not only clear cases of ecstasy, but also phenomena that are closely related to it. Something should also be said about the body-mind-issue, the relation between psyche and soma-an age-old problem in philosophy. There are almost as many theories about their relationship as there are philosophers. The materialists stress soma at the total cost of psyche; the idealists do the opposite. Of dualism, there are many different versions, for instance parallelism, which proposes that the two coexist without directly affecting each other. Without discussing any of these further, I will simply state that I here regard body and mind as two sides of the same coin; the same phenomenon seen either from the point of internal subjective experience, or from the point of external objective observation. When a change occurs in soma, a simultaneous change also occurs in psyche, and vice versa. There cannot be a change in one without a simultaneous change in the other. In the act of thinking, neural activity takes place in the brain. Although we do not know what a person is thinking by studying his brain waves, we do know that different types of thinking result in different types of brain waves (alpha and beta waves, etc.). The claim that there cannot be a change in psyche without a simultaneous change in soma is of course hard to prove, since our instruments are not, and perhaps never will be, sufficiently sensitive to register all the subtle changes in the human nervous system. But in my opinion it is the most plausible viewpoint, judging from the present scientific data. Whether one wants to call this dualism or materialism is a matter of taste. But this soma-psyche relationship is the basic assumption which I will use as the starting point for this discussion. Since mental states and physiological correlates always accompany each other, it is obvious that the human mind can be affected by external means, for instance by drugs. But the opposite is also true; mental changes affect the body, as they do in the case of psychosomatic diseases. Aldous Huxley was the first one to suggest that mystical experiences are directly related to physiological changes (Huxley, 1969; first published in 1954). He based his hypothesis mainly on his own experiments with mescalin. Huxley believed that adrenochrome, which is a product of a decomposition of adrenalin and has a chemical composition resembling that of mescalin, might be the cause of so called "spontaneous" mystical experiences, since this substance, he thought, might occur spontaneously in the human body in sufficient amounts (Huxley, ibid., 12). He also suggested that mystical experiences could be achieved by means other than exogenous or endogenous hallucinogenics. The breathing exercises of yogis, for example, might increase the amount of CO2 in their lungs and blood, and hence also in the brain (Huxley, ibid., 113). When the ascetics of medieval times used to beat themselves repeatedly, histamine was released into the blood, which according to Huxley (ibid., 120) might have caused an intoxication reminiscent of that achieved with hallucinogenic drugs. He explained the prevalence of mystical experiences in medieval times in a similar fashion: it could have been the result of severe lack of vitamins (Huxley, ibid., 1 17-1 19). In his proposals as to how the different ecstasy techniques work physiologically, Huxley was probably often wrong (a point to which I shall return). Modern research data have refuted many of his hypotheses, or at least rendered them unlikely. All this does not make Huxley less important; he started a new paradigm in the psychology of religion. We certainly have to agree with Huxley that physiological variables must be taken into account when we ponder the question of why religious practitioners all over the world have used such similar ecstasy techniques. They have altered their physical constitution by fasting or adhering to vegetarianism; they have changed their hormonal balance by living in celibacy; sometimes they have bombarded their nervous system with drugs. At times the physiological implications are more subtle and not so easily apprehended, as in the case of meditation, prayer and the use of music. The music might be slow and "soothing" such as one may hear in a Christian mass or in a Tibetan temple, or it can be fast and rhythmic, often combined with drumming and dancing, as in voodoo. Meditation, prayer and music are undoubtedly psychological rather than physiological, but studies of brain waves have made it clear that they also have physiological implications. Drugs have been used in all parts of the world as an ecstasy technique (Furst, 1972). How the hallucinogenics work, however, is not quite clear. Most researchers agree that they seem to interfere with the transmitter substances in the nervous system. The adrenochrome hypothesis, suggested by Huxley (1969; see also above), appears unlikely to be true-there does not seem to be enough adrenochrome in the human body to account for any radical effects. Instead it has been thought that LSD might interfere with the action of serotonin. In some situations LSD has been shown to act like serotonin, and in others to be a powerful antagonist to it; thus LSD might either facilitate or block the neurohumoral action of serotonin in the brain (Barron et al., 1971). But it is far from proved that the effects of LSD can be explained this way. It may be that LSD creates an imbalance among several different neurohumors. The question is still not settled. Even less is known about how fasting and vegeterianism work. There has been surprisingly little study of the physiological effects of reducing food intake and adhering to special diets, and even less of the psychological effects. EEG recordings obtained from the participants in a fasting march from Jyvaskyla to Helsinki in Finland three years ago showed more alpha activity after the march than before (Björkqvist, S.-E., 1980). This is a quite natural result of the participants being tired, and of course a combined result of both marching and fasting; in what proportions is impossible to say. That celibacy can also be considered as a "physiological" ecstasy technique has been almost overlooked by the psychologists of religion. It has not, to my knowledge, been discussed at length in the literature. The psychodynamic implications of sublimating the libido (in Freudian terms) have been discussed, but the physiological implications have been neglected. Still it is a fact that the vast majority of all widely-known mystics have been living in celibacy. In medieval times, when monasteries were common in Europe, mysticism flourished. When the number of monasteries decreased, mysticism also declined. Celibacy was of course only one factor of many, but nevertheless probably an important one. In Hinduism, celibacy or brahmacarya has always been a highly emphasized technique. How it works can at the present only be guessed at. But it is evident that celibacy must have a profound influence on hormonal balance in the body. Some authors (e. g., Ornstein, 1972) have suggested that, neurologically, religious experiences are a function of the right cerebral hemisphere. From the work of Sperry and Gazzaniga (Gazzaniga, 1971), among others, we know that the two brain hemispheres have, in part, very different functions. The left hemisphere is connected with the right side of the body, the right hemisphere with the left side. In most people, the left hemisphere is dominant-a good example being righthandedness. During childhood, the two brain halves develop partly different functions. For instance, the area of cortex dealing with hearing is in the left hemisphere connected with speech; the corresponding area in the right hemisphere is connected with the musical ear and the comprehension of music. Speech, logical thinking and mathematics are governed largely by the left hemisphere (Luria, 1978). The right hemisphere seems to be the more intuitive, artistic half of the brain. However, to claim that religious experience is governed by the right hemisphere would be to jump to conclusions. Ecstasy is often described as an extremely joyful experience; this pleasure must necessarily also have a physiological basis. It is of course too early to say anything for certain, but the discovery of pleasure centres in the brain (e.g., Olds, 1971) might offer an explanation. These pleasure centres are situated at different locations in the midline region of the brain, but mostly in the hypothalamus. If an electrode is inserted into the brain of an animal at a spot where a pleasure centre is situated, and through a special arrangement such as by stepping on a pedal the animal is able to give itself electric stimulation in that specific spot, something remarkable occurs; the pleasure is so intense that the animal will forget everything. It will no longer care about food or drink, and it will often simply stimulate itself until it dies. These same pleasure centres also exist in the human brain. Could it be that in the future we will find humans with electrodes inserted into their brain, giving themselves electric stimulation every now and then? A new, more horrible addiction, worse than heroin? Let us hope this will not be the case. But it is not far-fetched to suggest that when a person experiences euphoric ecstasy, it might, in some way or other, be connected with a cerebral pleasure center. The best known studies of ecstatic experiences utilizing physiological measurements have been the electro-encephalographic (EEG) investigations of meditation. A number of studies (e.g., Anand et al., 1961; Wenger & Bagchi, 1961; Kasamatsu & Hirai, 1963, 1969; Wallace, 1973; Banquet, 1973) have shown that the most typical finding during meditation is a general slowing down of the brain waves. Slow alpha waves with increased amplitudes, sometimes even still slower theta waves (which usually appear only during light sleep) are frequent during meditation, regardless of the type-yoga, zen, or TM. In one study, faster beta waves were more frequent (Das & Gastaut, 1955) but in this study the subjects used a special technique, Krya yoga, which involves strong concentration on the point between the eyebrows with the eyes crossed. Strong concentration is always correlated with beta waves in the EEG. And even in this study, the yogis in question had abundant alpha activity after finishing meditation. Another observation (Banquet, 1973) is that the deeper the meditation, the more synchronized this activity seems to be, so that the same type of activity takes place simultaneously all over the cortex. The neurons seem to fire off in the same rhythm, regardless of where they are located. Alpha waves are usually associated with a relaxed and positive mood. Other physiological measurements have corroborated this. During meditation, skin resistance is higher, which is a sign of released tensions. The amount of lactate in the blood decreases, which is also a sign of reduced tension (Wallace, 1973). Heart rate and breathing slow down. Taken as a whole, the entire metabolism slows down, with the person remaining in a state of peaceful rest. The question can be raised: How is it possible that by practising meditation a person can learn to increase, at will, the amount of alpha activity in his brain? Although alpha activity also appears in untrained subjects when they are relaxed and have their eyes closed, it has been shown (Wallace, 1973; Kasamatsu & Hirai, 1963, 1969) that the better subjects are trained in meditation, the more frequent and slower is their alpha activity; theta activity, which is still slower than alpha, generally appears only among trained meditators. Functionally, man has two nervous systems: one through which he can voluntarily control certain muscles of the body, and another called the visceral or autonomic nervous system (ANS). Through the ANS are governed the activity of the heart, the stomach and other internal functions. It has been thought that we are unable to control these voluntarily to even the slightest degree, but this has lately been shown to be false. Miller (1971) was the first to demonstrate that learning in the ANS can take place at least to some degree. For instance, through a feedback mechanism, subjects, whether they are animals or humans, can to a slight degree learn to slow down or speed up their heart beat. This phenomenon has been called biofeedback. Biofeedback can also be applied to the activity of the brain. It has been shown that people can learn to increase their alpha activity (e.g., Kamiya, 1969) or even their theta activity (Green, 1975) at will. In this learning process the person sits with electrodes attached to his head, through which brain wave activity is registered. Whenever alpha activity appears in the EEG, a special sound automatically registers through a loudspeaker; and when the alpha disappears, quite another sound is aired. In that way, the subject can acquire a "sense" for how alpha activity feels, and is slowly able to increase it at will. This can also have a therapeutic effect, reminiscent of that of meditation (Green, 1975). The experiments with brain wave feedback give a hint of how meditation works. In a way, meditation can be seen as a kind of biofeedback without the alpha activity monitored out through speakers; instead, the meditator listens to subtle inner signals. To help in this process he can use one of several meditation techniques which differ slightly depending on the religious tradition or group he belongs to. In India, breathing exercises have been used as an ecstasy technique. But also in zen, the counting of inhalations or exhalations has been used as a meditation technique (Kapleau, 1970, 32). As mentioned earlier, Huxley thought that breathing exercises could cause religious experiences by increasing the amount of CO2 in the brain. This is highly unlikely-breathing CO2 is a very unpleasant experience, which anyone knows who has been in a room with extremely bad air. There is another possible explanation, which l have suggested in an earlier work (Björkqvist, K., 1976). Breathing is an exceptional function in that it is controlled both by the ANS and the somatic or voluntary nervous system. Some breathing occurs automatically all the time, and we cannot at will stop breathing altogether. The ANS sees to that. But we can voluntarily change the rhythm as well as the depth of our breathing. Moreover, breathing is closely related to a number of functions governed solely by the ANS, such as heart beat, perspiration, and various mechanisms related to emotions. As a consequence, breath control or simply being attentive to one's breathing would probably be the easiest biofeedback technique to learn, since it does not involve any direct or difficult learning in the ANS. If meditation increases alpha activity, then listening to slow, soothing religious music, like Christian hymns or Tibetan temple music, can be expected to have a somewhat similar effect: a slowing down of the brain waves. But how can we then explain that the complete opposite-fast, rhythmic music combined with drumming and dancing-has been a popular ecstasy technique in many cultures? Pavlov (1928), in his conditioning experiments with dogs, had already observed something which he called the ultraparadoxical phase. Both when the dogs were totally overstimulated and when in certain stages of drowsiness, there occurred a distortion of the effects of the conditioning stimuli. The positive stimuli lost their effect, and the negative became positive. Sargant (1951, 1957) suggested that something similar could be the case in man when sudden political or religious conversion occurred. He interpreted this phenomenon, which he called "transmarginal inhibition", brought on by these transmarginal stimuli (=stimuli exceeding the limit), as some kind of collapse in the reactiveness after intense mental tension or excitement. This has direct relevance in the study, for instance, of the physiological effect of voodoo dancing. Oswald (1959) found to his surprise that when he repeatedly gave strong electric shocks to his subjects, they fell asleep! He also found (Oswald, ibid.) that the signs of sleep in the EEG could repeatedly come and go in rhythm with regular stimuli at intervals of only a few seconds. When people were dancing to the rhythm of a popular dance band, they could actually fall asleep for a few seconds while still moving. In another experiment (Oswald, 1960), he taped the eyelids of his subjects so that they were unable to close their eyes. He then gave them electric shocks and bright visual stimulation to the rhythm of a blues band. All his subjects fell asleep. Voodoo dancing, and similar practises, can easily be understood in terms of the inhibition caused by transmarginal stimulation. All the time they are dancing, dancers are on the border between sleep and wakefulness, at times actually sleeping while dancing. It is easy to understand that visions can be seen in such a state. Sundén (1967) has interpreted the experiences of zen monks in similar terms to Sargant and Oswald. The spiritual practice of prayer, on the other hand, seems to have a lot in common with meditation. Neither prayer nor meditation are in themselves necessarily ecstatic experiences; but they are practices during which ecstasy frequently occurs. It is therefore reasonable to consider them as ecstasy techniques. The effect of prayer on the body has not been studied very much with physiological methods. When Mallory (1977) used EEG in her investigation of monks and nuns at prayer, she found no increase in alpha activity during prayer compared with the activity recorded in a control situation-. She did find, however, that extraverted subjects had more abundant alpha activity than others, and that the abundance of alpha correlated positively with contemplation and negatively with neuroticism. Synchronization of alpha activity was another interesting point; it was reduced when subjects had difficulties in contemplating. Contemplation was thus associated with both alpha abundance and alpha synchronization. Mallory, summing up her results, says that subjects who were good at contemplation tended to have the same degree of alpha abundance as experienced yoga or zen practitioners. The only possible difference was that the alpha activity of her subjects remained the same in the control situation, sitting with closed eyes, but not praying, as in the experimental situation, sitting with closed eyes, contemplating. Having abundant alpha activity seemed to be the natural state for these subjects when relaxed (Mallory, 1977). In a study in progress, I have been measuring EEG, GSR (skin conductance and skin potential), heart beat and eye movements (EOG) of ten persons while they pray. All belong to a sect calling themselves "rukoilevaiset" (The Prayers), whose members live in South West Finland. The members of this sect pray regularly and often. The subjects were first told to sit still with their eyes closed, and simply to tune themselves in on being close to God, but not actually to pray. This was called the contemplation condition. They were then told to pray as they normally did, either with words or silently, whichever they preferred. Some typical results are seen in figures 1-6. Two records are shown for three subjects. During the contemplation condition, alpha activity was common among most subjects. A typical case is shown in fig. 1. One subject (fig. 3) even had very slow theta activity. |

|

|

|

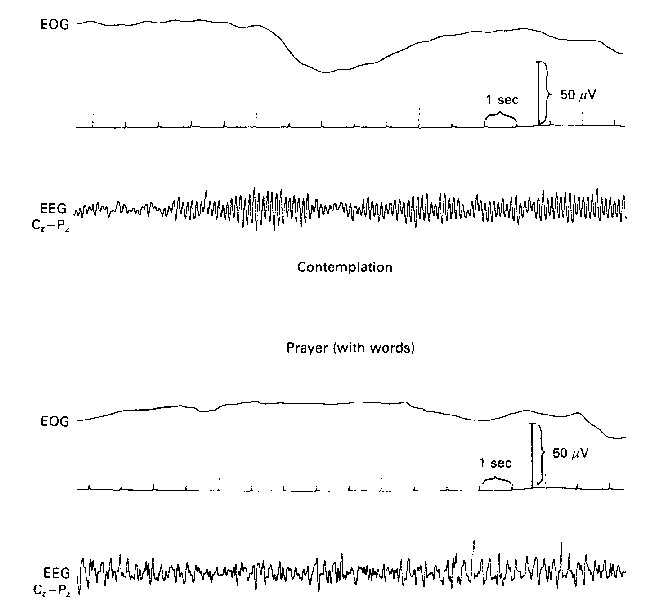

Figs. 1-2. EEG and EOC recordings of a middle-aged man during contemplation and prayer. Note the symmetrical alpha during the contemplation condition. During prayer, the alpha is blocked by faster, irregular beta activity. Beta always appears during concentrated mental activity. |

|

|

|

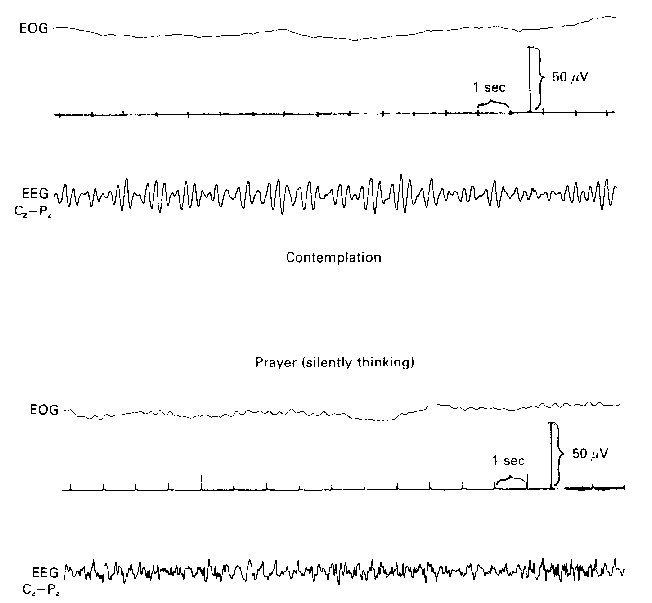

Figs. 3-4. EEG and EOG recordings of a middle-aged man during contemplation and prayer In the contemplation condition, very slow theta activity appears. In the prayer condition. the theta is blocked by fast beta waves due to the concentration. although the subject is sitting silently with his eyes closed. There are almost no eye movements in either condition. |

|

|

|

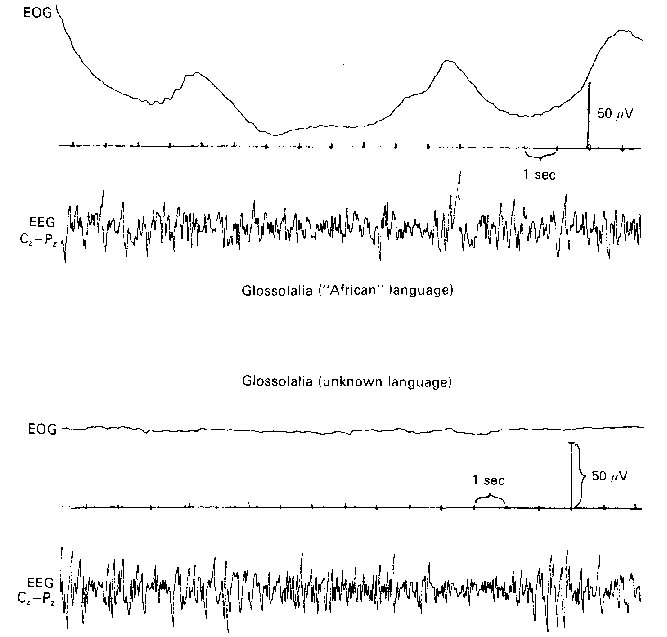

Figs 5-6. EEG and EOG recordings of a middle-aged woman while speaking in tongues; two different languages. Fast beta activity is dominant in the EEG. The spike-like waves occurred when she aspirated phonemes loudly, and seem to originate from verbal motor cortex. Note the rolling eye movements during the speaking of the "African" language. |

|

One of the subjects asked if she could be allowed to speak in tongues. Though this is not a usual practise in this particular sect, she had acquired the habit. I was of course delighted. So she spoke in two "languages". While switching to something she described as an "African" language, she immediately started doing large, irregular rolling movements with her eyes (fig. 5). When she switched to the other language, the eye-rolling immediately stopped (fig. 6). In this study, prayer and contemplation certainly mean something different from that in Mallory's investigation. Her subjects were Catholic monks and nuns, who used totally different techniques to my subjects, who were saying their prayers in a traditional, Lutheran manner. Nevertheless, the results are compatible, and seem to indicate that Christian prayer in a contemplative state generates abundant alpha, in certain cases even theta activity. Active praying, on the other hand, blocks the alpha and replaces it with beta activity. It might be added that the electrodermal measurements indicated that praying relieved psychological tension. I have previously mentioned or described several ecstasy techniques, all of which have one thing in common: all affect the body in one way or another. I have also suggested possible mechanisms by which they might work. In fact, they are so many and varied, that it might seem confusing. But is only one explanation right, and are all the others wrong? Can it be, for example, that religious ecstasy is attained only by some mechanism triggering off changes in the balance of the transmitter substances? Or is it reached only via a change in the hormonal balance, or only by a slowing down of the brain waves, or is a pleasure centre activated? I am not proposing that one of these possible explanations is correct, and that all the others are wrong. Future knowledge will probably refute some suggestions (if not all of them) and corroborate others. My suggestion is that an ecstatic experience can be reached by many different means, which might affect the body in slightly or quite different ways. Whatever the physiological basis of the experience-and as I said, it might vary in different cases-we must not neglect the cognitive side. An experience is something that happens in our consciousness. We interpret in a certain way, depending on how we have been ''programmed" by our social background and past experiences. Schachter & Singer (1962) with their widely accepted two-factor theory of emotion, proved that at least in the case of physiological arousal, the cognitive interpretation is of utmost importance. An aroused person might interpret his experience as anger, fright or euphoria, depending on what he expects. They showed this by injecting their subjects with adrenalin and telling them that they had received a new drug called "suproxin''. Because the researchers gave different information to different subjects about how the drug would work, the subjects tended to behave differently in the expected direction compatible with the information they had received-although all subjects showed signs of physiological arousal. The possibility cannot be excluded that by a feedback loop the cognitive interpretation might in turn have affected physiological functions. But Schachter and Singer's experiment clearly demonstrated the power of expectations. When a person is using an ecstasy technique, he usually does so within a tradition. When he reaches an experience, a traditional interpretation of it already exists. The Hindu mystic experiences unity with Brahma, while the Catholic mystic sees visions of Jesus and Mary. It is true, however, that within the Christian tradition, too, the experience of unio mystica resembles the Hindu samadhi. But the power of cognitive expectations can clearly be seen when we study the literature of the mystics. In some cases, a person might obtain an ecstatic experience "by mistake". Maybe the person unintentionally triggers one of the, probably many, physiological mechanisms through which such an experience can be reached. In such cases, it is not rare to find that the person later, by reading, looks for an interpretation and maybe finds it within a tradition. The well-known Swedish "mystic of Vällingby" was perhaps such a case (Dahlén, 1976). Much is still unknown about the physiological basis of the experience of ecstasy. We still deal mostly in vague guesses and suggestions. However, because knowledge of the central nervous system is continuously increasing, it is likely that in the future we can base our speculations on firmer ground. The science of psychophysiology is developing rapidly; this development will of necessity also be reflected in the psychology of religion.

|

|

|

|

|